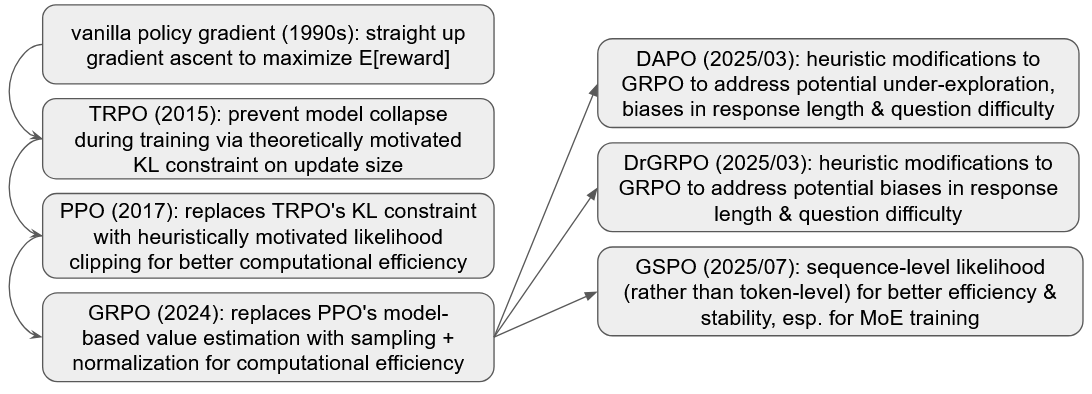

Intuition for some policy gradient methods for LLMs

TLDR: intuitive motivation for policy gradient algorithms that people currently use for reinforcement learning training of LLMs (e.g. PPO, GRPO, and descendants), starting from basics

0. setup

Notation:

- \(x\) is the input, i.e. a sequence of tokens representing the user prompt submitted to the LLM

- \(y\) is the output, i.e. the sequence of tokens produced by the LLM in response to this input, and \(y_t\) is the \(t\)th token produced

- \(r(x,y)\) is a reward function that defines the quality of this response (e.g. if \(x\) is a math question and \(y\) is an answer, maybe \(r(x,y)=1\) IFF answer is correct)

- \(\pi_{\theta}\) is an LLM with parameters \(\theta\), interpreted as a policy: i.e. \(\pi_{\theta}(y_t\mid x, y_{<t})\in [0,1]\) is the probability the LLM outputs token \(y_t\) in the \(t\)th position given the input prompt \(x\) and all output tokens prior to \(t\)

All of the methods here aim to optimize the expected reward:

\[\begin{equation} J(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{x, y\sim \pi_{\theta}(\cdot\mid x)} r(x,y) \label{trueobj} \tag{0} \end{equation}\]- where the expectation ranges over:

- all inputs \(x\) we care about

- for each input \(x\), the distribution of responses \(y\) as produced by the LLM with parameters \(\theta\)

These methods all work by:

- construct some proxy for this expected reward

- optimizing this proxy, typically via first-order methods (e.g. compute gradient wrt \(\theta\) & using it to update \(\theta\) via gradient ascent or ADAM or whatever)

1. vanilla policy gradient (REINFORCE)

Nobody does this in real life, but this is a textbook policy gradient algorithm that everything else builds off of

This works by maximizing this proxy objective, which intuitively can be understood as an estimate of the log-likelihood-weighted average goodness of every token produced by our LLM:

\[\begin{equation} \hat{J}_{vanilla}(\theta)=\hat{\mathbb{E}}_{x, y~\sim \pi_{\theta}(\cdot \mid x)}\left(\sum_{t}\log\pi_{\theta}(y_{t}\mid x, y_{<t})\hat{A}(x,y,t)\right) \label{vanilla} \tag{1} \end{equation}\]- \(\hat{\mathbb{E}}_{x, y~\sim \pi_{\theta}(\cdot \mid x)}(stuff)\) means:

- sample a bunch of inputs \(x\)

- run each one through the LLM \(\pi_{\theta}\) to get a corresponding \(y\)

- do stuff to each (x,y) pair

- then compute the average of the stuff

- \(\hat{A}(x,y,t)=r(x, y) - b(x, y_{<t})\) is an estimated “advantage” function

- this \(b(x, y_{<t})\) is a baseline that measures how easy the task of picking \(y_t\) is:

- e.g. given input \(x\), if the output that’s already been produced (\(y_{<t}\)) constitutes a very good answer to \(x\), then \(b(x, y_{<t})\) should be high to capture the fact that it’s very hard to mess this up going forward

- i.e. this could be a value function that you estimate

- this is a variance reduction technique: we’re giving the algorithm more signal by not allowing an output token \(y_t\) to coast on the success of its predecessors

- this \(b(x, y_{<t})\) is a baseline that measures how easy the task of picking \(y_t\) is:

this functional form looks pretty intuitive, though it comes via a slightly unintuitive route (see e.g. lecture 5 of the Stanford RL course):

- compute the gradient of Eq. \(\eqref{trueobj}\)

- do some algebraic manipulations on this gradient (which I didn’t find to be very intuitively useful)

- reconstruct an objective function that then generates this gradient when differentiated

2. TRPO: KL-constrain updates for better stability

One of the pitfalls of vanilla policy gradient is its instability: sometimes, you take a gradient step and the LLM quality dramatically drops, never to recover again

TRPO (trust region policy optimization) achieves this by maximizing a likelihood-ratio adjusted average advantage, subject to not changing things too much

Objective: “maximize the sampling-ratio adjusted average goodness of every output token” \(\begin{equation} \hat{J}_{TRPO}(\theta)=\hat{\mathbb{E}}_{x,y\sim \pi_{\theta'}(\cdot \mid x)}\sum_{t}\frac{\pi_{\theta}(y_{t}\mid x, y_{<t})}{\pi_{\theta'}(y_{t}\mid x, y_{<t})}\hat{A}(x,y,t) \label{TRPO} \tag{2.1} \end{equation}\)

Constraint: “without changing the policy too much” \(\begin{equation} s.t. \quad \hat{\mathbb{E}}_{x,y\sim \pi_{\theta'}(\cdot \mid x)}[ KL\left(\pi_{\theta}(\cdot\mid x, y_{<t}), \pi_{\theta'}(\cdot\mid x, y_{<t})\right) ] < \delta \label{TRPO_constraint} \tag{2.2} \end{equation}\)

Interpretation:

- \(\theta'\) are the old parameters

- the objective is relatively intuitive:

- generate a bunch of samples with our old LLM \(\pi_{\theta'}\)

- reweight each sample by the ratio of probabilities, so that it’s as if we’re sampling from the our updated LLM \(\pi_{\theta}\), without having to manually do it

- generate the average advantage, i.e. measure of how good each output token \(y_t\) is (see section 1 for intuition on what that means)

- the constraint just says that our old vs new LLMs can’t be too different in terms of implied probabilities of next tokens:

- \(\pi_{\theta}(\cdot\mid x, y_{<t})\) is a probability distribution over possible tokens \(y_t\), i.e. a multinomial distribution

- this KL divergence is then just: \(\sum_{z} \pi_{\theta'}(z\mid x, y_{<t}) \log\left(\frac{\pi_{\theta'}(z\mid x, y_{<t})}{\pi_{\theta}(z\mid x, y_{<t})}\right)\)

- where this sum is over all possible tokens \(z\)

- this quantity is naturally interpretable as the “distance” between two distributions, i.e. it’s always nonnegative, and zero only when \(\pi_{\theta}\) and \(\pi_{\theta'}\) are identical

- this is then averaged over the \(x\) and \(y\) sampled for the objective above

How this achieves the goal:

- there’s some theory that guarantees that so long as our gradient step sizes aren’t too big, we’re guaranteed to not fall of a cliff

- intuitively, the likelihood ratio makes the objective unbiased, since it corrects for sampling probabilities so that it’s as if we’re sampling according to \(\pi_{\theta}\) rather than the old \(\pi_{\theta'}\)

- and the KL divergence being small means that the two policies are close enough that this correction doesn’t blow up

- The derivation effectively comes down to:

- noting that the difference between the true expected reward at two \(\theta\) values is \(J(\theta) - J(\theta')\approx J_{TRPO}\) in Eq.\(\eqref{TRPO}\) above

- then showing that that \(J_{TRPO}+ApproxError>0\) for \(\theta\) sufficiently close to \(\theta'\)

- (see lecture 7 of the Stanford RL course, slide 17ish)

- that is, Eq.\(\eqref{TRPO}\) is a proxy objective we can continually optimize to monotonically improve the true reward

- But practically:

- the theoretically montone-improvement-guaranteed updates are too small

- the monotone improvement theory is for the infinitely discounted case with rewards each period, as opposed to the setting here where we have a finite number of steps (i.e. the output max token length) and a single reward for the entire answer (though there may have been some recent work extending this to the episodic case)

- and also, people don’t do this, because conjugate gradient + line search is complex

Another nice property of TRPO is that in both the objective and the constraint, the \(y\) is sampled via the old policy \(\pi_{\theta'}\)

- as in, look at both Eq.\(\eqref{TRPO}\) and \(\eqref{TRPO_constraint}\): all the samples are drawn from the old policy \(\pi_{\theta'}\)

- compare with Eq.\(\eqref{vanilla}\), which technically should be done by sampling from the new policy \(\pi_{\theta}\)

- so, when in real life, we actually sample from the old policy & do our gradient update, this might cause some further stability issues

3. PPO: clipping instead of trust region for computational efficiency

TRPO has some drawbacks:

- hard to implement:

- solving the constrained optimization problem requires solving a large system of equations via conjugate gradient

- vs e.g. just doing a simple gradient update or some other simple first-order method

- sample efficiency: still need to re-sample outputs every time the model gets updated, as doing multiple steps here would move us out of the trust region

PPO aims to have the similar robustness to TRPO, but better sample efficiency & be easier to implement

We’ll just look at the clipped objective, which just takes the TRPO objective and supplements it with a clipped version of that same thing:

\(\begin{equation} \hat{J}_{PPO}(\theta)=\hat{\mathbb{E}}_{x,y\sim \pi_{\theta'}(\cdot \mid x)}\sum_{t} \min \left( w(\theta \mid x,y,t)\hat{A}(x,y,t), \text{clip}(w(\theta \mid x,y,t) , 1-\epsilon, 1+\epsilon)\hat{A}(x,y,t) \right) \label{PPO} \tag{3} \end{equation}\) where:

- \(w(\theta \mid x,y,t) = \frac{\pi_{\theta}(y_{t}\mid x, y_{<t})}{\pi_{\theta'}(y_{t}\mid x, y_{<t})}\) is the likelihood ratio for observing token \(y_t\) between the new vs old LLM params

- \(\hat{A}(x,y,t)\) is an estimate of the advantage, i.e. measure of how good each output token \(y_t\) is (see section 1 for intuition on what that means)

- \(\epsilon=0.2\) or something like that

The intuition for this formula is relatively straightforward:

- \(w(\theta \mid x,y,t)\hat{A}(x,y,t)\): this same as in the TRPO objective in Eq.\(\eqref{TRPO}\)

- \(\text{clip}(w(\theta \mid x,y,t) , 1-\epsilon, 1+\epsilon)\hat{A}(x,y,t)\) is effectively a poor-man’s trust region

- the clipping function just sets the value of \(w\) to \(1+\epsilon\) or \(1-\epsilon\) if it exceeds these bounds

- note that this is equivalent to dropping observations where the likelihood ratio exceeds these limits, because clipping replaces \(w(\theta)\) with a constant so that when you take the gradient, it contributes nothing

- recall the the TRPO constraint in Eq.\(\eqref{TRPO_constraint}\) basically wants this \(w(\theta \mid x,y,t)\) to be close to 1, i.e. for the old & new LLMs to assign equal-ish probability to the next token, on average

- … so dropping data (from the gradient update) where this likelihood ratio is too extreme feels like it might achieve something similar

- I think this was a purely heuristic move, but there’s been some recent work that maybe clipping is theoretically good?

- the clipping function just sets the value of \(w\) to \(1+\epsilon\) or \(1-\epsilon\) if it exceeds these bounds

- the minimum of these two: assume the worst about observations beyond our clipping bounds

- when the likelihood ratio is within the clipping bounds, then the two versions are identical => everything is normal

- when the likelihood ratio is outside of this bound, then this min function takes whichever of the clipped vs non-clipped versions is less favorable

- intuitively, this amounts to assuming the worst for things outside of the clipping bounds:

- e.g. if the advantage is positive, and the new policy assigns much higher probabity to this observation: basically drop this observation, i.e. we don’t trust it, not going to let it influence our gradient

- e.g. if the advantage is negative, and the new policy assigns much higher probability to it, then we DO NOT clip here, instead letting this information influence our gradients

The main benefit of this is that it’s an unconstrained problem that you can do first-order optimization on, vs the more difficult constrained optimization of TRPO

- this is easier, because conjugate gradient is hard

- also better sample efficiency, by taking multiple gradient steps before re-sampling data:

- note that Eq.\(\eqref{PPO}\) samples \(y\) from the LLM with old params \(\theta'\)

- and given that we’re handwaving away the actual monotone improvement bounds, it feels fine to do multiple gradient updates with old sampled data before re-sampling

- so, this isn’t quite a free lunch: better sample efficiency comes at the cost of theoretical guarantees on monotone improvement

4. GRPO: advantage estimation via sampling + normalization

In PPO, the advantage estimate \(\hat{A}(x,y,t)\) is often computed by a separate neural network, which is computationally costly

GRPO was introduced by deepseek in 2024 for training LLMs to do math: it just gets rid of this separate neural network by estimating the advantage in a more straightforward way:

- instead of generating just a single response for each input \(x\), generate a “group” of responses \(\{y^i\}_{i=0}^G\)

- recall that \(\hat{A}(x,y,t) = r(x,y) - b(x, y_{<t})\), where \(b(x, y_{<t})\) is some baseline measure of how “easy” it is to complete the response to \(x\) given already-generated tokens \(y_{<t}\)

- so you can just average within each group to get a baseline, which gives us the GRPO objective:

\(\begin{equation} \hat{J}_{GRPO}(\theta)=\hat{\mathbb{E}}_{x}\hat{\mathbb{E}}_{y^1,...,y^G\sim \pi_{\theta'}(\cdot \mid x)} \frac{1}{G}\sum_{i=1}^G \frac{1}{\mid y^i\mid}\sum_{t} \min \left( w(\theta \mid x,y^i,t)\hat{A}(x,y^i), \text{clip}(w(\theta \mid x,y^i,t) , 1-\epsilon, 1+\epsilon)\hat{A}(x,y^i) \right) \label{GRPO} \tag{4} \end{equation}\)

- where the advantage is just the reward of each sampled \(y^i\), normalized by the mean & stdev of the other \(y\)s in that group:

\(\displaystyle

\hat{A}(x,y^i) = \frac{r(x,y^i) - \text{mean}\left[r(x,y^1),..., r(x,y^G)\right]}{\text{stdev}\left[r(x,y^1),..., r(x,y^G)\right]}\)

- note that this advantage is no longer at the token level: i.e. this expression has no dependence on \(t\), so that every token in an output \(y^i\) gets the same advantage value

- so there’s intuitively some ‘information’ loss here by replacing the more nuanced advantage estimate with this simple one

- \(\mid y^i\mid\) represents the number of tokens in output \(y^i\) (the GRPO paper actually refers to this normalizing by the number of tokens as being present in PPO)

- and everything else is as in PPO:

- \(w(\theta \mid x,y^i,t) = \frac{\pi_{\theta}(y^i_{t}\mid x, y^i_{<t})}{\pi_{\theta'}(y^i_{t}\mid x, y^i_{<t})}\) is the likelihood ratio of generating token \(y^i_{t}\) given input \(x\) and prior output tokens \(y^i_{<t}\)

- \(y^1,...,y^G\sim \pi_{\theta'}(\cdot \mid x)\) means that all our response are generated wrt old LLM parameters \(\theta'\)

- the clipping and min logic is the same

5. DAPO: some heuristic adjustments to GRPO

This bytedance paper from 2025 introduces DAPO, which makes some heuristically motivated adjustments to GRPO:

- Clip-Higher: allow higher clipping in the increase-likelihood case, so as to promote more exploration (i.e. be more permissive when old policy puts very low probability on an action)

- this is because in PPO / GRPO clipping means an observation \(x, y_0, ..., y_t\) gets dropped if the new-parameter LLM puts a much higher probability on the selected token \(y_t\) than the old-parameter LLM (see the PPO section for more disussion)

- but this feels weird? like if our model just under-weights certain output tokens, and we have a set of new parameter values that seem like they produce better outputs here… why are we dropping these observations?

- the clipping mechanism essentially amounts to putting zero trust in these observations: the advantage function is an estimate, and thus noisy

- but surely there’s some information here that we can make use of?

- so, DAPO is more permissive when it comes to clipping

- Dynamic Sampling: if a group of responses is uniformly good or bad, that’s not informative, so just remove those & continue sampling until we get enough non-uniform ones

- the authors indicate that this problem becomes increasingly severe for GRPO as training proceeds, since the model gets increasingly good at stuff, and so always generates correct answers to more & more inputs => updates are decreasingly informative

- Token-Level weighting: treat all tokens in a group of samples equally, rather than down-weighting tokens in long responses

- in GRPO Eq.\(\eqref{GRPO}\), there is a \(1/\mid y^i\mid\) term, which means that tokens from longer answers get less weight

- this incentivizes short answers when correct answers (i.e. for observations where advantage >0)

- and also incentivizes long answers when incorrect (i.e. where advantage <0)

- some other stuff to further penalize excessively long answers

this generates a new objective: \(\begin{equation}\displaystyle \hat{J}_{DAPO}(\theta)=\hat{\mathbb{E}}_{x}\hat{\mathbb{E}}_{y^1,...,y^G\sim \pi_{\theta'}(\cdot \mid x)} \frac{1}{\sum_{i=1}^G \mid y^i \mid}\sum_{i=1}^G\sum_{t} \min \left( w(\theta \mid x,y^i,t)\hat{A}(x,y^i), \text{clip}(w(\theta \mid x,y^i,t) , 1-\epsilon_{low}, 1+\epsilon_{high})\hat{A}(x,y^i) \right) \label{DAPO} \tag{5} \end{equation}\) where

- \(\epsilon_{low} = 0.2\)ish, \(\epsilon_{high} = 0.28\)ish, so as to encourage exploration by being more lenient when we have an improvement to the policy that puts more weight on good samples

- the samples \(y^1,...,y^G\sim \pi_{\theta'}(\cdot \mid x)\) are generated as before, BUT with the additional requirement that any samples where all the rewards \(r\) are uniformly 0 or 1 get dropped

- the \(\frac{1}{\mid y^i\mid}\) term in GRPO is replaced with a \(\frac{1}{\sum_i \mid y^i \mid}\) up front

- this amounts to treating each input \(x\) equally, and distributing that mass across all outputs \(y^1,...,y^G\) in proportion to the number of tokens, rather than treating each \(y\) the same so that tokens from longer response get less weight

- and everything else is as in GRPO:

- advantage estimate: \(\hat{A}(x,y^i) = \frac{r(x,y^i) - \text{mean}\left[r(x,y^1),..., r(x,y^G)\right]}{\text{stdev}\left[r(x,y^1),..., r(x,y^G)\right]}\)

- \(w(\theta \mid x,y^i,t) = \frac{\pi_{\theta}(y^i_{t}\mid x, y^i_{<t})}{\pi_{\theta'}(y^i_{t}\mid x, y^i_{<t})}\) is the likelihood ratio of generating token \(y^i_{t}\) given input \(x\) and prior output tokens \(y^i_{<t}\)

- \(y^1,...,y^G\sim \pi_{\theta'}(\cdot \mid x)\) means that all our response are generated wrt old LLM parameters \(\theta'\)

6. DrGRPO: also some heuristic adjustments to GRPO

This paper from 2025 seems to do something pretty similar to DAPO, in making some modifications to GRPO to address these potential issues:

- same observation as in DAPO, that the GRPO objective in Eq.\(\eqref{GRPO}\) has as \(1/\mid y^i\mid\) term, which means that tokens from longer answers get less weight, incentivizing short answers when right & long answers when wrong

- the stdev in the denominator of the GRPO advantage function up-weights observations with low stdev, i.e. where all the answers are either right or wrong

- I guess intuitively you can go either way on this: maybe you should up-weight these questions, since if you get a hard question right you want to strongly reward it, and likewise if you get an easy question wrong

- but, on the other hand, for the kind of rewards that these people are using (e.g. math questions with rewards being 1 if correct), it doesn’t seem necessary to do this normalization since everything is same order of magnitude anyway

so they just get rid of these two things: no more normalizing by the token length of each response, and no more stdev in the advantage computation:

\(\begin{equation} \hat{J}_{DrGRPO}(\theta)=\hat{\mathbb{E}}_{x}\hat{\mathbb{E}}_{y^1,...,y^G\sim \pi_{\theta'}(\cdot \mid x)} \frac{1}{G}\sum_{i=1}^G \sum_{t} \min \left( w(\theta \mid x,y^i,t)\hat{A}(x,y^i), \text{clip}(w(\theta \mid x,y^i,t) , 1-\epsilon, 1+\epsilon)\hat{A}(x,y^i) \right) \label{DrGRPO} \tag{6} \end{equation}\) where:

- advantage estimate: \(\hat{A}(x,y^i) = r(x,y^i) - \text{mean}\left[r(x,y^1),..., r(x,y^G)\right]\)

- everything is like GRPO:

- \(w(\theta \mid x,y^i,t) = \frac{\pi_{\theta}(y^i_{t}\mid x, y^i_{<t})}{\pi_{\theta'}(y^i_{t}\mid x, y^i_{<t})}\) is the likelihood ratio of generating token \(y^i_{t}\) given input \(x\) and prior output tokens \(y^i_{<t}\)

- \(y^1,...,y^G\sim \pi_{\theta'}(\cdot \mid x)\) means that all our response are generated wrt old LLM parameters \(\theta'\)

7. GSPO: sequence-level instead of token-level

This 2025 paper from the Qwen people argues that GRPO’s token-level importance sampling just adds noise, and instead moves to doing everything at the output level rather than the token level

\(\begin{equation} \hat{J}_{GSPO}(\theta)=\hat{\mathbb{E}}_{x}\hat{\mathbb{E}}_{y^1,...,y^G\sim \pi_{\theta'}(\cdot \mid x)} \frac{1}{G}\sum_{i=1}^G \min \left( s(\theta \mid x,y^i)\hat{A}(x,y^i), \text{clip}(s(\theta \mid x,y^i) , 1-\epsilon, 1+\epsilon)\hat{A}(x,y^i) \right) \label{GSPO} \tag{7} \end{equation}\)

- note that there’s no more sum over tokens for each output \(y^i\): this objective function is no longer at the granularity of tokens, but rather entire sequences (i.e. full outputs = \(x, y^i\) pairs)

- but the per-token likelihood ratio has been replaced by a per-sequence one: \(s(\theta \mid x,y^i) = \left(\frac{\pi_{\theta}(y^i\mid x)}{\pi_{\theta'}(y^i\mid x)} \right)^{1/\mid y^i\mid}\)

- the advantage is the same as in GRPO: \(\hat{A}(x,y^i) = \frac{r(x,y^i) - \text{mean}\left[r(x,y^1),..., r(x,y^G)\right]}{\text{stdev}\left[r(x,y^1),..., r(x,y^G)\right]}\)

- there was a bit of a weird mismatch in GRPO, where you had this likelihood ratio defined at the token level, but the advantage was at the sequence level

Note that they normalize by the length of the output, because the raw sequence level log likelihood ratio is going to be \(\pm \infty\), as each output is up to tens of thousands of tokens, and when you aggregate up the per-token log likelihood ratios things are invariably going to blow up in one direction or the other:

\(s(\theta \mid x,y^i)

= \left(\frac{\pi_{\theta}(y^i\mid x)}{\pi_{\theta'}(y^i\mid x)}

\right)^{1/\mid y^i\mid}

= \exp \left(

\frac{1}{\mid y^i\mid} \sum_t\log\left(

\frac{\pi_{\theta}(y^i_{t}\mid x, y^i_{<t})}{\pi_{\theta'}(y^i_{t}\mid x, y^i_{<t})}

\right)

\right)\)

the \(1/\mid y^i\mid\) is thus crucial here: makes this an “average log likelihood ratio across tokens in this response”, which won’t be mechanically concentrated at \(\pm \infty\)

The authors were particularly motivated by difficulties of GRPO for MoE training:

- in mixture of experts networks, which experts get activated can vary a lot even for small parameter updates, leading to highly unstable token-level likelihood ratios => a lot of info gets dropped

- they overcame this previously via “routing replay”: fixing expert activations when computing likelihood ratios, which feels kind of hacky

- GSPO obviates the need for this hack

Appendix: is this exercise even useful?

we’ve operated entirely in this high-level intuition space so far, but:

- this is a field where implementation details matter a lot: see e.g. this 2020 paper on how seemingly minor implementation details of TRPO & PPO actually drives most of the reported gains of these methods

- it’s also unclear whether the authors have the correct intuitions for their own methods: this stuff is all pretty handwavy, so the intuition in these papers might just be wrong

- also, this field is all about the data, so over-focusing on algorithms might not be that useful

so, this sort of high-level algorithmic understanding probably doesn’t go super far in terms of actually being able to build this stuff